My Plural Is People

Anndee Hochman

“Zachary Kahn-Molina, do you have siblings?”

Mr. Rattrazino paused, stub of yellow chalk cinched between his second and third fingers like the suave, chain-smoking lead of a 1930s movie. Rattrazino—mostly, we called him “Mr. R,” though a few smart-asses (usually after they’d bombed a test) muttered “Mr. Rat” behind his back—was old-school that way. He declined the offer of a smart board even after the PTA held a gazillion bake sales and magazine drives to outfit every classroom with “21st-century technology,” forgetting that only people who’ve spent most of their conscious existence in a different century bother to name the one we’re in.

For us, high-school kids conceived on the lip of the millennium—the moment when everything was supposed to apocalyptically crash but instead went on ticking—the 2000s are just our lives. The years in which we had the weird and tragic luck of being born. The water we thrash in.

“The rising-sea-level-full-of-dead-coral-rapidly-warming-ocean water,” Khady would say if she were here checking off her math requirement, instead of spending 4th period doing independent study in environmental feminist philosophy.

Not that it mattered. Khady was brilliant enough to get into any college she wanted, even if she’d only squeaked through Algebra 2 thanks to weekly tutoring sessions from yours truly. It was a trade: Every Tuesday night, she’d bring extra of what her Grandma Delores had made—Southern vegan soul food, she called it—and we’d fork up seitan gumbo and dirty rice while reviewing binomial equations. Khady was grateful because I had a knack for explaining. I was grateful because ever since the divorce, both my moms were too sad to cook.

“Zachary, it’s a simple question. Do you have brothers and sisters?” Mr. R may have been retro about technology and fashion—I mean, the guy wore suspenders, with a maroon bow tie on school spirit days, and pants he probably bought when Bill Clinton was president—but he wasn’t actually that old. Young enough, anyway, to remember that teenagers needed time to untangle their thoughts. He’d pose a problem and wait in the itchy silence, pinching the chalk, while we worked it through.

But this morning, we hadn’t even opened our books. Kids were still straggling into the room in twos and threes, plopping backpacks on the floor, digging for pencils, and Mr. R was doing his top-of-the-hour chat, describing a podcast he’d heard on the way to school about how math aptitude runs in families. Apparently, the experts were divided on the nature/nurture question—that is, were some kids good at math because they got a crazy-smart math gene from their mom or dad, or were they good at it because the people who raised them played Baby Einstein in the nursery and talked differential equations over dinner?

Mr. R was just wondering, with that podcast in mind (and my freakish talent for getting As in a class most kids sweated through), if other people in my family also had a gift for numbers. For instance, my siblings?

Siblings? I was still stuck on his little news brief about the podcast. Nature versus nurture? Genes going mano a mano against the environment? Why did it have to be a face-off, bitter as divorce court, instead of a slow-mo ballet? What if a baby got the super-smart math DNA but then was raised by wolves—or, say, adopted by people who couldn’t figure a restaurant tip without a calculator? Or maybe the reverse: The baby inherits a full set of humanities-tilting chromosomes, then the parents die and the kid’s court-appointed guardian is the winner of a Fields Medal—like the Nobel Prize for math. Would the kid go on to be some kind of numerary genius? And who would get credit for that?

Welcome to my life: a quiz of either/or questions when the answer is always “all of the above.” How many times has someone asked, “Which one’s your mom?” then looked confused when I answer, “Both.” Every September, a pile of emergency contact forms where I scribble out “father” and write “mother” and “mother.” Racial group check-offs that list Caucasian, Black, Hispanic or Asian but not Jewish/Puerto Rican/Irish or una mezcla, as my mom Ana likes to say.

Even the gender box, the one most people think is a no-brainer, gave me stomachaches. I’d hover my pencil over “male” and think of all the ways I wasn’t: I hated arm-wrestling and loved Sondheim and turned into a weepy mess watching Coco every time. Then I’d start to mark “female,” but that felt like trespassing; I didn’t have boobs or periods or construction workers calling me “bitch” when I refused to smile. The whole setup seemed like a failure of imagination: How come we’ve got 27 different kinds of breakfast cereal, but only two genders to choose from?

This is why I never look in mirrors. Because I don’t have words for what I see.

So, what about a write-in vote, a create-your-own-adventure answer? Was I gender-fluid? That made me think of antifreeze. Gender nonconforming? Sounded like I’d misbehaved. What do you call the kid who knocked over his best friend—that was Khady, from the get-go—in order to grab the princess gown out of the dress-up bin in preschool and now, at 17, wasn’t sure what he wanted to wear or, for that matter, who he wanted to kiss? What was the politically sensitive, spot-on, 21st-century gender term for still-trying-to-figure-it-out?

There wasn’t a word for me, just like there wasn’t one for my relationship with Ana’s ex-husband, the guy she was with before she married (and—ouch, okay—divorced) my other mom. Joe and Ana were together for three years when they both realized they were queer—it was the old days, remember, before kids started saying they were bi or trans in middle school—and split up so warmly that, later, Joe became part of our family, the guy who brought homemade biscuits for Thanksgiving and taught me, at age 7 to calculate probabilities so I could win at rock/paper/scissors. When I was little, I always wanted a family name for him: Papa Joe, Uncle Joe, Cousin-once-removed Joe. “I’m just your regular Joe,” he’d shrug. But I was too young to get the joke.

Khady liked to say that the main difference between us was that she loved questions while I searched for answers. “You gotta get comfortable with shades of gray, Z,” she’d say. “Or, in my case, shades of brown.” In 6th grade, when the earnest let’s-save-the-poor-urban-kids English teacher had us do family trees, Khady grabbed every darkish crayon in the Crayola box—burnt sienna, umber, copper, bronze—and drew hers with warty arms that looked like they’d barely survived the latest (hello: climate change is real) hurricane. “Should I draw the branch where my great-great-great-uncle was lynched?” she asked. And the white teacher turned even whiter.

Me, I was using colored pencils I sharpened like darts, trying to make my tree gorgeous and precise: my mom Ana’s side and all the Latinx cousins, my mom Jen’s side, great-grandparents named Esther and Shmuel. But what about the half of the tree that belonged to my donor and his people? All I had was a twig: California Cryobank specimen #573.

In February, when I turned 18, I’d be able to write to the sperm bank and find out his name. My moms were on board with that—they were the ones who chose a willing-to-be-known donor back when they first started trying to make a baby, so I could have the option of contacting him, later if I wanted to. What they didn’t know, because they were still preoccupied with post-divorce fallout like splitting up the Broadway show CDs and redrafting their wills, was that I’d already tried sleuthing the guy out online, using a handful of clues from the cryobank’s paperwork.

My mom Jen had saved it—she saves everything, even my kindergarten journals that are mostly raisin figures with stick legs and giant flowers and crayoned captions like “I lov chrees.” From the file, I knew #573 had studied forestry and lived in the Pacific Northwest—my bet was Corvallis, Oregon State University—before he started donating sperm. That he liked lizards and the color teal. That he’d answered the sperm bank’s questions in spiky print, his lower-case i’s topped with dashes instead of dots. The first time I saw that, when I was 11, I stopped breathing for a second. That’s how I made my i’s. Is handwriting hereditary?

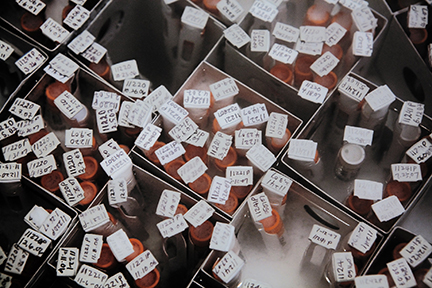

I hadn’t had any luck finding #573, but had stumbled onto the Donor Sibling Registry, a giant online bulletin board for families who used donor sperm or donor eggs. If you register, and you know the cryobank or clinic or doctor your parents used along with the donor’s code number, you can see if there are other people who had kids with the same sperm. It cost money to join—$99 for a one-year membership—and I’d been saving every dime I got from tutoring 8th graders in geometry, but the price wasn’t the only reason I’d held back.

If I had half-brothers and -sisters, and the odds were in favor of a resounding yes on that question, then maybe one of them, a sib who’d turned 18, had already found #573. And maybe the guy had decided that one kid was enough and he didn’t want to know the rest of us. Or what if a bunch of them had tried to locate him and slammed into the same dead ends I did? What if I met the sibs and it was like a hall of mirrors, a dozen weirdly angled reflections of me? Would that mean I’d found my tribe… or lost myself? Or what if nature was batting zero, and the sibs were nothing like me? I could tolerate being a stick-out at school; it would feel worse to be an outlier with my own half-kin.

Last Sunday—shuttle-day, when I move from Ana’s apartment in South Philly to Jen’s row house in Germantown or vice-versa—I decided to take the plunge, metaphorically speaking. I was in my room, pretending to do homework, when I got onto the DSR, put the membership fee on Ana’s credit card (I’d pay her back later), clicked California Cryobank, then scrolled through the list to donor #573.

Six other families had already registered. There was “labrysduo,” with a boy born March 2, 1999, and a girl born October 24, 1996. “Veganmama” had twin girls, born in June 2000. I did the math: 16 months older than me; two-and-a-half years younger. I kept reading, my fingers so slick they left beads of sweat on the track pad, my heart banging in my chest. Another boy, born four days before my own birthday. “SapphoSisters,” with a girl six months younger than me. Two more boys, in the same family, 20 months apart. And a note at the bottom: “This donor has a total of 17 offspring from this clinic.”

I slapped my laptop closed. The room wobbled a little, and I had that might-faint feeling that I sometimes get at the eye doctor’s office or when I’m watching a movie with too much blood. I grabbed my phone and called Khady. “This better be good,” she answered, “’cause I’ve got 50 pages of Judith Butler to read for a paper on gender and performativity, due tomorrow… hey, Z, you’re not saying anything. You okay? You singing the Sunday afternoon divorced-kid blues?”

My voice came out like a croak. “I just looked on that thing I was telling you about, the DSR. There are 17 of them. Of us. Including me. Siblings. Half-siblings, technically.”

“Shit. You gonna e-mail them?”

“I don’t know. Maybe. Not tonight. I mean, what do you say to the brothers and sisters you’ve never met? Hi, I’m Zach, we come from the same splooge?”“You want me to come over?”

“No, you have that paper. And I have a math thing. Also, I’m supposed to make dinner tonight. Fettucine. It’s Jen’s favorite. She hates Sundays.”

“You know you can call anytime, Z. I’ll be here, wrassling Ms. Butler.”

That was three days ago. Now, here I was, the 4th-period bell about to clang and my classmates opening their calculus books and Mr. R posing a question your average 3-year-old should be able to answer.

“Zachary. Mr. Kahn-Molina. Do you have any brothers and sisters?”

Ask me anything else, I thought. Ask me about the Fibonacci sequence. Tell me to write a proof of Fermat’s little theorem or recite the first 15 digits of pi from memory. I took a sticky breath. Maybe my vocal cords were paralyzed. My mouth started to say yes, but the word got caught on its way out, like there was too much explanation knotted to its tail. My face swiveled left, then right, my cheeks on fire. My stomach hurt. It was 11:43 on the morning of November 12th. The beginning of something. Questions without answers.

No, I lied.